Carmakers warn the government must renegotiate its deal with Brussels

There is no hope for Britain’s car industry … or at least no hope of maintaining the scale and productive capacity that this bedrock of the UK manufacturing sector could boast before the Covid-19 pandemic.

It’s downhill from here.

Brexit is an issue – whatever the business secretary, Kemi Badenoch, says – because being inside the single market and sitting at the top table in discussions about the industry was always going to give the UK more heft when the inevitable Europe-wide carve-up over electric car factory locations happened.

Government policy – or, more accurately, the almost complete lack of it – is probably a much bigger factor when the survival of the entire sector is at stake, as it clearly has been since the Brexit referendum.

And the car industry itself is a problem, especially the dominant players in the UK, which have too often preferred to play chicken over subsidies with a government that lacks a plan and is incapable of making more than incremental, piecemeal decisions.

Things have come to a head after a row with Stellantis, the world’s fourth largest carmaker, which was created when the US-Italian combo Fiat Chrysler merged in 2021 with the PSA Group, better known as the owner of Peugeot and Citroen. The group, which also makes Vauxhall vehicles, employs more than 5,000 people in the UK, including 1,000 at its electric van factory in Ellesmere Port, Cheshire, and 1,200 at its Luton plant.

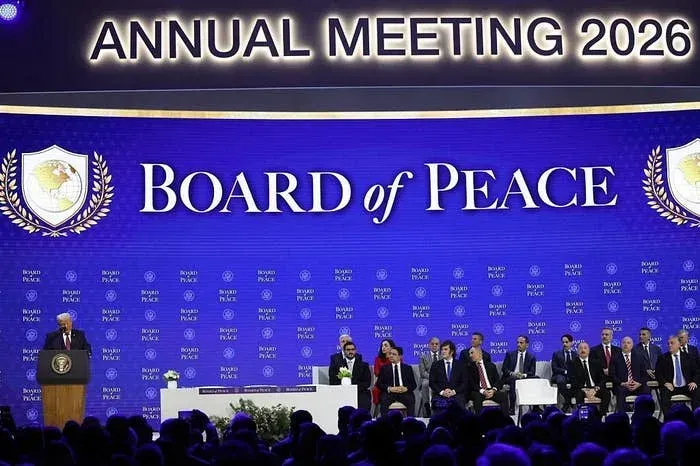

The company has warned that a commitment to make electric vehicles in Britain is in jeopardy unless the government renegotiates its Brexit deal with the EU to maintain existing trade rules until 2027. Jaguar Land Rover (JLR) has said much the same. So has Ford.

Like a billionaire shopping at Harrods, every car company wants lots of free stuff before they commit to expensive investments. Nissan secured an undisclosed government bung when it recommitted to north-east England before the UK left the EU at the end of 2019. JLR has since secured financial government support, as has Stellantis.

At the heart of the dispute, say the car firms, is the trade and cooperation agreement (TCA) between London and Brussels. It was signed in 2020 and includes “rules of origin” that require 40% of an electric vehicle’s parts by value to originate in the UK or EU in order for it to qualify for trade without tariffs. Most batteries come from China, so it’s a struggle to satisfy the rules. When the threshold rises to 45% next year and 55% in 2027 it will be impossible, carmakers say.

Brussels officials could reasonably blame the car companies and individual governments for a lack of readiness, or at least those that have so far failed to invest.

Have I made another point that the Brexit was the wrong decision?